I don’t have a complete technical explanation of this, and is more my experience tuning boards over the past year. It’s really hard to describe without a board in front of me as demonstration, but I’ll try my best…

Generally speaking, the limiting factor for almost every board’s turning radius(assuming wheel bite isn’t an issue) happens when the bushings compress and stiffen up, prevent any more compression, preventing the truck from rotating further(especially boards with stiff bushings). This is very apparent on channel trucks, especially Lacroix Hypertrucks that have the stock/default stiff bushings. (part of the carvey, great feeling of Tito’s trucks is they turn a lot further before the bushing stiffens up. In fact, it happens so deep into the turn that he needed to add a 3d-printed lean limiter).

For a given truck/bushing, this stiffening is going to happen at roughly the same “angle of turning”. See picture for the direction I’m talking about. (This is most applicable to trucks that have locked-in geometry, ex. Tito Duality, channels, 3-links, etc. It’s more different with RKP and especially TKP, and I lack experience in that area)

Take the extreme example of a board with very very high hanger angles for “maximum turning”(say, 60 degrees). When you start to lean the deck, the trucks will aggressively turn, very quickly compressing the bushings. The hangers are the ones “moving into” the bushings. You might hit the point of maximum bushing compression at, say, 10 degrees of deck leaning.

Take the opposite extreme example of a board with very very low hanger angles(say, 10 degrees). When you start to lean the deck, almost nothing will happen to turn the trucks, so nearly all of the compression of the bushings will come from the deck “moving into” them. You’re likely to hit 45+ degrees of deck lean before hitting the point of maximum bushing compression, assuming you don’t bottom out your deck first.

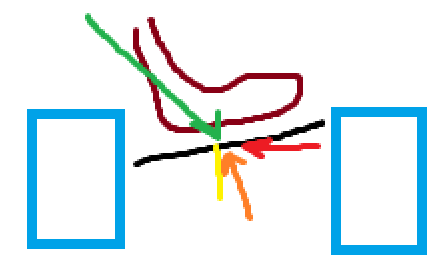

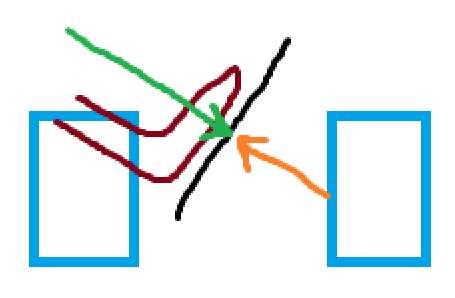

MS Paint to my rescue. Hopefully these diagrams make sense and aren’t confusing. I drew them exaggerated to help demonstrate my point.

I drew the diagrams looking from the rear of a board, turning left-

Blue = Tires/wheels

Black = Deck

Maroon = your feet

Green = force from your weight when turning/carve

Orange = force from the deck, pushing back on you

Red = force from your grip tape, resisting your feet from sliding.

Yellow = Moment distance

When you go to ride the first example (with the high angles), when you take a turn… imo it’s undesirable for a bunch of reasons.

- There’s a component force that wants to pull your foot parallel to the deck of your board(red), and fights your turning. Considering your standing platform is (almost certainly) above the pivot point of the trucks, having your weight pushing outward wants to rotate the board opposite direction that you’re trying to lean. This fights the part of your weight that’s working to lead the deck (and turn the board)

Tangentially related, I think one of the (many) reasons the Stooge V5 frame is so dominate in racing is the low ride height makes the moment(force * distance to pivot, yellow) of this force small, so the board isn’t fighting your inputs. - The faster you take a turn, the further you need to lean off the board (shocking, I know). When the deck doesn’t want to lean very much, this leaning need to come from your ankles. IDK about you, but my ankles can’t do this

The other option is to stand on your tippie toes, but this will reduce the control you have over the board. - This force component(red) is normally resisted by your griptape. But if your foot slips for any reason(road bump, sweaty feet, loose shoes, old griptape, gravel, etc), your weighting of the board changes, changing this turning angle. This is more of an issue when on your tippie toes, and can contribute to an unstable, unplanted feeling.

- Unsurprisingly, high angles are inherently more sensitive to you inputs to the deck. This can lead to a board feeling overly “twitchy” or “darty”, and being unstable at speed.

When you go to ride the second example (with the low angles), the force of your weight goes directly into the deck. This removes that undesirable side force, negating/reducing a lot of the negative points presented above.

- Most notably, for the purposes of this discussion, you can put more of your weight into compressing the bushings, because less/none of your weight will be trying to fight that side force/moment. This increases how much you can compress the bushings, increasing the “angle of turning”, decreasing your turning radius.

- Being evenly planted gives you much better control over the board. You’re not getting all weight onto the edges of your deck, trying to turn. Instead, your weight is much more evenly distributed between your heels and toes (if that makes sense). Being more evenly weighted, I"m able to make quick adjustments to my trajectory around a corner, feeling out the edge of traction.

This leads to a more surfy, carvy feeling, where you can really grab the board and whip it around in a way that you can’t with steeper hanger angles.

This is DKP, but my single parking space challenge is a great extreme example of what I mean. Pay attention to how extreme my deck angle is.

IMO, No reason to have an your turning be limited “artificially” by bushings, when you can run them softer or with wedge plates to extend the turning capabilities to the mechanical limits of the board setup (as increasing the mechanical limit usually entails a very large design change to the board)

I think this is why I’ve like all of my boards set up where their turning is limited by the mechanical properties of the board.

- Ankle Wreacher and Nothing Fancy scrape the enclosure

- My Kaly hits the mechanical endstops of the trucks

- My Tynee gets wheelbite on my shreadlights.

However, this setup philosophy is personal preference, and from someone that rides more track then street. Lots of riders out there are happy with their stiff hypertrucks. Different board setups for different folks. If it feels good to you, then it’s a good setup. ![]()